In my many years of teaching yeshiva guys I have found that one of the topics that suffers from the most difficulty and confusion is the topic of the transmission of the Torah and the masora (the oral interpretation of the Torah). We all know that the written Torah came first, right?

Well… that’s actually wrong!

We all know that Rebbe Yehuda hanassi wrote the Mishna, right? Well,… sort of! That’s not exactly true either!

How about the Gemara?

See, that’s the funny thing about yeshiva (or any institution of “higher” learning, which I stress because I am referring to people who are there to learn and not those who are there to feel important): if you don’t stop to actually think about what you are learning you tend to entirely miss the point of the learning in the first place!

No topic is more confusing, in this regard, than the history of Torah. It is my hope that in this article I will succeed to begin making some seder (organization), so that this topic can be fully understood.

In this regard I wish to focus on the topic of the written Torah and it’s relationship with the oral one.

We all know that the Torah and the cheesecake descended from Heaven intertwined! It is for this reason that Jews throughout the centuries have eaten cheesecake exclusively on Shavuout.

Just kidding.

However, I am sure that we all know the explanation of the Magen Avraham zt”l as to why we have a minhag (custom) to eat cheesecake on Shavuot. To paraphrase the explanation it is because, like all good Jewish stories, that after the Torah was given to us the first thing that we wanted to do was to eat! In fact all of Jewish history could be summed up by the phrase “They tried to kill us, they didn’t succeed – Let’s eat”! But in truth, that doesn’t account for all of the other times that we appreciate food. We ALWAYS have appreciated food and even to this day we take every opportunity to commemorate all things with food. It’s our go-to passion.

Anyway.

The Magen Avraham said that the Jews came back from receiving the Torah at Sinai and immediately the conversation turns to food. “I’m so hungry sweetie! I could eat a cow!” says the husband to his wife. “Well”, she says back, “even though I would just LOVE to accommodate you, we just now got the Torah! Didn’t HaShem just teach us that in order to eat meat we have to first shecht it (ritually slaughter), check it (for lesions and other wounds and the like, which make the animal unfit), and then we have to remove the veins, salt it… did I miss anything? Anyway, that will take us a REALLY LONG TIME”! “But I’m hungry NOW”, complains the husband. To which his wife says “Let him eat cake”. Or, rather, “Well all we have ready to eat now is some milk products”. So in commemoration of that wondrous occasion we now have the custom of eating milchik (dairy) in honor of the chag (festival) of Shavuos.

Except that that’s wrong.

It’s wrong for a very simple reason.

Which is that HaShem DIDN’T give us the entire Torah at one shot.

He didn’t plop the whole scroll of five books into our laps and say to us “From now on you are all responsible to keep everything that is written in here. If you don’t know it by tomorrow – you’re dead”! He actually was very lenient and patient with us.

The proof to that can be found throughout the five books themselves.

Let’s start with parshas Yisro, where the Torah enumerates TEN, (count them!), commandments. Even those initial ten weren’t really so unfamiliar to them. Most of them are covered by the seven Noahide laws. The others were first introduced to them a little bit in advance, at a place called Marrah, where Bnei Yisroel were given several parshios of the Torah to learn in preparation of the giving of the Torah.

Take parshas Shemini, for example, where the Gemara in Tractate Bava Basra tells us that there were eight new parshios that were given to us on that day.

However, this doesn’t mean that there were actual written documents that were given over to the people of Israel during their stay in the desert. In fact this topic is one of the many issues which our sages, ob”m, argue over. As the Gemara in Tractate Gittin 60a teaches, Rabbi Yochanan and Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish argued on this issue. The opinion of Rabbi Yochanan (R”Y) is that the Torah was given to the children of Israel in a piecemeal fashion during their stay in the desert. This means that every time that Moshe wanted to teach something to the people he would first dictate to them the relevant verses and then he would begin to expound the halachos and the deeper meanings of the text. The opinion of Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish (R”L) is that the Torah was given over all at once.

However, it is agreed upon by BOTH of these great men that during the forty years in the desert there was no weekly Torah reading from the scroll, as there was no scroll to read from. If you would ask me “Rabbi Ben Zeev! How in the world can you say that? Don’t you know that the Gemara in Tractate Megilla 31a says that Moshe established the public reading of the Torah? (Yes, clearly I do know that one). What about the Gemara in Tractate Bava Kamma 82a which also says something similar”?

I will answer: that Moshe made the takkanah (enactment, literally “fix”) to read the Torah publicly, at certain fixed times, just before his death, when the sifrei Torah were first delivered to the tribes to use.

If you would continue to probe and ask: what about the verses that were quoted, which refer to a much earlier time during the sojourn in the desert?

To this I would answer simply that the problem was noted early on during the stay in the desert, a real takkanah was not enacted until such time as the nation was given a sefer Torah to read from at fixed times. Indeed the problem noted in the Gemara in Bava Kamma of the people not learning Torah for at least three days was only a problem before the Torah was given, which is the time noted in the verse that the people “traveled for three days and did not find water”. They immediately came to the place called Marrah (mentioned above) where they were first introduced to some talmud Torah, even though they were not yet commanded to keep the mitzvos that they were learning about. After the giving of the Torah, which occurred a short time after Marrah, there was plenty of Torah learning going on on a daily basis. (I mean, what else was there to do in the desert back then?) The only time that the issue of talmud Torah resurfaced was right before Bnei Yisroel entered the land of Israel, when they began to live life in this world like “regular” people. NOW there was a need for public Torah reading!

Therefore, it turns out that of the two Torah’s it is not even a question that the ORAL one came first. It was by the oral Torah that our people lived in the desert, not by the written one.

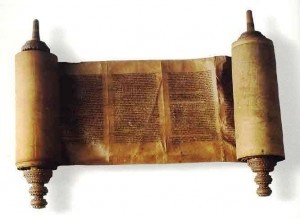

The Written one was given to the people by Moshe Rabbenu just before his death, on the plains of Moav, when each and every tribe received a scroll personally written by Moshe himself. One was also given over into trust by the tribe of Levi, which was considered to be THE authoritative version of the text.

This is explicit in the Torah (Deuteronomy (Devarim) 31:9) “And Moshe wrote this Torah, and he gave it to the Kohanim, the sons of Levi, they who carry the Ark of the Covenant of G-d, and to all of the elders of Israel”. It was only just before Moshe’s death that the first sifrei Torah were first given to the people of Israel.

Therefore, the Torah either was entirely introduced to the people just before Moshe’s death, or it was put together, organized and then re-introduced to us as a completed project just before the people entered the land of C’naan.

Our masorah teaches us that all of the five books that today compromise the Torah were written by Moshe himselfi. The Gemara in Tractate Sanhedrin teaches based on this, and it is brought down le’halacha by the Rambam in the laws of the foundations of the Torah, in his famous “13 principles”, that anyone who denies this precept is an apostate.

The only question that remains is the topic of whether the scrolls were written in Old Hebrew or in Ashurian script (the script in which the sifrei Torah are written today). The gemara in Tractate Sanhedrin (21a-b) brings an entire machlokes (argument) on this topic, and I certainly don’t feel it my place to enter that arena. But the truth is that it really doesn’t matter. According to everyone the Torah today is written in kesav Ashurit, (the STA”M writing) and it has the full holiness and authority of the original.

As opposed to all of the “other” “Torah”s of the world, (i.e. the New Test(ament), the Koran and the Writ of Morman) there are practically no variants of the Torah’s script. This is NOT true of the Christian and Moslem texts, both of which suffer from gross discrepancies in the actual text, as opposed to small changes which are attributed to “copy errors”ii and have no real bearing on the reading, nor on the interpretation of the verse.iii This despite the fact that the Hebrew Bible, as it known colloquially, is clearly the older of all of the ancient texts.

Based on all of the above we can now begin to understand what the Mishna in Avos (1:1) means when it says “Moshe received the Torah at Sinai”. For despite the fact that Moshe, himself, DID receive the entirety of the Torah at Sinai, he didn’t – and couldn’t – give it over to the people immediately. It was a process that took time to slowly teach the people the entire Torah. It was only AFTER the learning of the entire Torah during their stay in the desert that the people received the written Torah, which then became the central focus of, and the basis of all, future Torah learning of the people.

It is for this reason that a significant amount of the Mishna and Talmud, (which we will, with HaShem’s help, speak about in the next articles), isn’t based on the verses of the Torah, but rather the correlation of the teaching to the verse is sought after usually after the fact.

iThe Gemara in Tractate Bava Basra tells us that there is some argument among the Tannaim as to whether or not Moshe himself wrote the last eight verses of the Torah, those verses that describe his own death. According to one opinion it was Yehoshua, (Joshua) who wrote the last eight verses.

iiFor more on this topic please check out: Christian Bible> https://www.quora.com/What-should-Hindus-know-about-lower-Criticism-of-the-Christian-Bible-II?redirected_qid=1416736 which brings several “juicy” bits showing how the New Test has clear contradictions. See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textual_variants_in_the_New_Testament for a very comprehensive list of the textural variants. Quaran> See http://godorabsurdity.blogspot.co.il/2015/01/the-bible-vs-quran-jay-smith-vs-shabir.html or http://www.unchangingword.com/textual-variants/ and http://www.answering-islam.org/authors/shamoun/quran_compilation.html . As opposed to all of the above the Torah, despite the very small textural quirks, almost all of which are from either having extra letters or missing letters in a word, which don’t even change the meanings of the words, truly has zero variants.

iiiEven our greatest detractors agree on this issue. The only changes are in extra letters or missing letters, things that have no, or very little bearing on the verse. There aren’t even any changes of, for example, a lamed (ל) to a mem (מ), which would have a significant bearing on the interpretation of the verse.

You must be logged in to post a comment.